Posted: Wed Jan 28, 2009 12:45 pm

I've put together this article in response to several recent discussions on this forum. I'm about to submit it to the Bulletin but it will be months before it appears in that, so I though I'd post it here first to keep the conversational ball rolling.

From Prehistoric to Historic Cattle – a reply to Beryl Rutherford.

Beryl’s article in the Summer 2008 Bulletin was an interesting read but, unfortunately, promulgated some very outdated views. As the DCS’ resident archaeologist, I thought it might help to summarise some current thinking.

To begin with, Prehistoric can be broken down into something less amorphous than everything prior to Julius Caesar’s invasion. Until roughly 10,000BC, Europe was in the grip of a succession of glacial periods, or the Ice Age. Britain was largely covered with ice. People used stone tools, generically known as Palaeolithic. The wild cattle were Bos primigenius or the Aurochs, which were very large animals, roughly 1.9m withers height. The ice then melted and plants, animals and people colonised the land exposed by the retreating ice sheets. Sea levels rose with the addition of the meltwater so some species, for example the aurochs, failed to reach places like Ireland before the land bridge was submerged. The people living in Britain were hunters and gatherers, still using stone tools, known as Mesolithic. Aurochs were certainly hunted, with bones recovered from the famous site of Star Carr in the Vale of Pickering. About 4000BC there was a profound change to a farming lifestyle, still using stone tools, known as Neolithic, but also using pottery. These farmers had domestic livestock that must have been introduced to Britain from Europe in boats, as the English channel had flooded. Sheep and goats are not native to northern Europe so are unequivocal imports. The early domestic cattle not much smaller than the wild aurochs, so it was unclear whether cattle had been brought in or were domesticated locally from wild aurochs. Recent advances in DNA profiling clearly show that the Neolithic domestic cattle differ from the aurochs found in Britain, so the farmers had brought their cattle with them and did not cross breed with the wild cattle. Some 2000 years later, by the end of the Neolithic and start of the Bronze Age, the domestic cattle had further reduced in size. Some of this reduction in size could be due to the presence of a form of dwarfism in Neolithic cattle. A calf humerus from a Neolithic site at the Knap of Howar in the Orkneys clearly exhibits dyschondroplasia.

It used to be thought that the Neolithic farmers only used their cattle for beef and that draught oxen and dairy cattle were part of a “Secondary Products Revolution” associated with the later Bronze Age. An exciting range of research projects utilising innovative scientific techniques, including analysing food residues in pottery, are demonstrating that Neolithic farmers were milking their cattle and making a range of dairy products.

Technology advanced with the advent of metallurgy based on copper alloys, hence the name Bronze Age for the period spanning roughly 2000-700BC. During this period the British aurochs became extinct, probably because of humans destroying the preferred habitat of the aurochs rather than hunting them. Only 25 years ago, a conference paper proposing cattle dairying at the Bronze Age site of Grimes Graves, based on the age profile of the cattle bones with elderly females and infant calves, provoked heated debate and outright denial. Nowadays the controversial has become mainstream thinking.

Several points stand out here as pertinent to the Dexter. Humans deliberately bred smaller cattle in antagonism to the default size of both the wild ancestor, the aurochs, and the earliest domestic cattle. The small cattle included examples with a genetic dwarfism. Humans have been actively selecting for dairy production, in association with small size, for several thousand years.

The Iron Age (no prizes for guessing why so named!) commenced roughly 700BC in Britain and ended with the Roman invasion of 43AD. Iron Age archaeological sites are far more abundant than those of the more remote past, with certain hillforts still dominating modern landscapes. The Butser Ancient Farm project was designed to quantify the productivity of Iron Age arable farming, with the livestock being a secondary academic consideration but invaluable for public appeal and “cute factor”. Peter Jewell, a respected zooarchaeologist and later a founding member of RBST, was asked to advise on appropriate breeds. The Dexter was suggested as the only modern breed then available that approximated to the archaeological finds of cattle bones. Peter Jewell made it very clear at the time that small Kerry cattle would have been a better option but the parlous state of all rare breed cattle in the 1960’s meant that this was not possible. The Kerry had become too tall and the Dexter, though a better size, was too chunky in build.

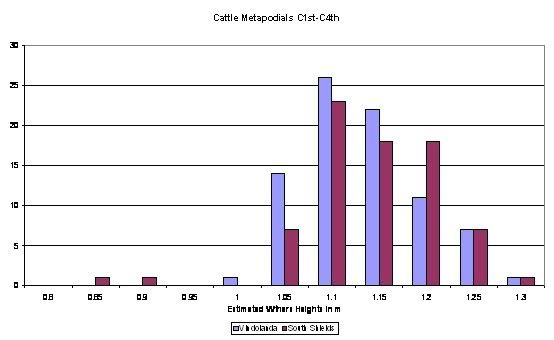

Roman forts in northern England produce cattle bones in abundance, in comparison to the native Romano-British farmsteads which are generally sited on soils where animal bone does not survive. The graph below shows the range of withers heights estimated from the cattle metapodials, or cannon bones, from Vindolanda in the mid-section of the hinterland of Hadrian’s Wall and South Shields on the coast as the eastern defence. Both populations show a normal bell curve distribution with sufficient overlap to suggest no major difference in population between the two groups. However the range is important with examples both of the very tiny animals, that are affectionately referred to as “cow kittens” by some Dexter breeders, and very large animals at the other extreme. It cannot be emphasised too strongly that such a range is “normal” in biological terminology, irrespective of whether the very small animals may, or may not, be carriers of dwarfism. The fact that the shortest animals from South Shields fall below 0.98m, which is 2 Standard Deviations from the mean of 1.12m, could suggest the possibility of a form of dwarfism being present. What is clear is that this extremely small type, though present, was not being actively selected for, in contrast to the modern Dexter. This graph demonstrates one possible outcome of a strategy that has been suggested to reduce the incidence of achondroplasia in the modern Dexter, by eliminating the use of carrier bulls. Two possible carrier cows might be represented in a sample of 76 bones from South Shields. No unviable calves would be produced and the presence of carrier cows would continue at the same negligible incidence

Over the past 200 years, livestock breeders have interfered with the biologically normal range by endeavouring to breed animals that fit within a reduced range of height variation. In the Dexter this has been towards the smaller end of the range, but the same foundation population could equally have been bred towards the larger end of the range. In effect, this is how evolution works but the process is considerably speeded up by controlled breeding. The concept of a “level herd” is, in archaeological terms, a very modern concept.

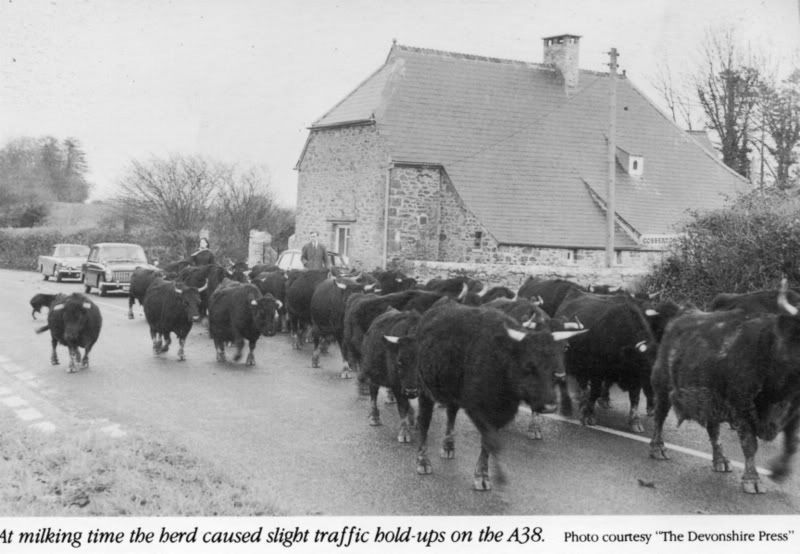

The photograph above of the Doesmead herd in 1966, from Ted Neal’s book, is a very important image, showing a herd where selection for dairy production appears to have been considerably more important than looks. There is an interesting range of small and large, chunky and slender animals. This picture gives an idea of what the archaeological cattle represented in the graph could have looked like. The Doesmead herd further emphasises that selection in the Dexter for herds where all the animals are more or less the same size is a very recent phenomenon. It is therefore not surprising that, irrespective of the presence or absence of the dwarf gene, the modern Dexter should still exhibit a range of sizes both between herds and within herds, such as my own, where parameters other than height are seen as more important for selection and retention of breeding stock.

From Prehistoric to Historic Cattle – a reply to Beryl Rutherford.

Beryl’s article in the Summer 2008 Bulletin was an interesting read but, unfortunately, promulgated some very outdated views. As the DCS’ resident archaeologist, I thought it might help to summarise some current thinking.

To begin with, Prehistoric can be broken down into something less amorphous than everything prior to Julius Caesar’s invasion. Until roughly 10,000BC, Europe was in the grip of a succession of glacial periods, or the Ice Age. Britain was largely covered with ice. People used stone tools, generically known as Palaeolithic. The wild cattle were Bos primigenius or the Aurochs, which were very large animals, roughly 1.9m withers height. The ice then melted and plants, animals and people colonised the land exposed by the retreating ice sheets. Sea levels rose with the addition of the meltwater so some species, for example the aurochs, failed to reach places like Ireland before the land bridge was submerged. The people living in Britain were hunters and gatherers, still using stone tools, known as Mesolithic. Aurochs were certainly hunted, with bones recovered from the famous site of Star Carr in the Vale of Pickering. About 4000BC there was a profound change to a farming lifestyle, still using stone tools, known as Neolithic, but also using pottery. These farmers had domestic livestock that must have been introduced to Britain from Europe in boats, as the English channel had flooded. Sheep and goats are not native to northern Europe so are unequivocal imports. The early domestic cattle not much smaller than the wild aurochs, so it was unclear whether cattle had been brought in or were domesticated locally from wild aurochs. Recent advances in DNA profiling clearly show that the Neolithic domestic cattle differ from the aurochs found in Britain, so the farmers had brought their cattle with them and did not cross breed with the wild cattle. Some 2000 years later, by the end of the Neolithic and start of the Bronze Age, the domestic cattle had further reduced in size. Some of this reduction in size could be due to the presence of a form of dwarfism in Neolithic cattle. A calf humerus from a Neolithic site at the Knap of Howar in the Orkneys clearly exhibits dyschondroplasia.

It used to be thought that the Neolithic farmers only used their cattle for beef and that draught oxen and dairy cattle were part of a “Secondary Products Revolution” associated with the later Bronze Age. An exciting range of research projects utilising innovative scientific techniques, including analysing food residues in pottery, are demonstrating that Neolithic farmers were milking their cattle and making a range of dairy products.

Technology advanced with the advent of metallurgy based on copper alloys, hence the name Bronze Age for the period spanning roughly 2000-700BC. During this period the British aurochs became extinct, probably because of humans destroying the preferred habitat of the aurochs rather than hunting them. Only 25 years ago, a conference paper proposing cattle dairying at the Bronze Age site of Grimes Graves, based on the age profile of the cattle bones with elderly females and infant calves, provoked heated debate and outright denial. Nowadays the controversial has become mainstream thinking.

Several points stand out here as pertinent to the Dexter. Humans deliberately bred smaller cattle in antagonism to the default size of both the wild ancestor, the aurochs, and the earliest domestic cattle. The small cattle included examples with a genetic dwarfism. Humans have been actively selecting for dairy production, in association with small size, for several thousand years.

The Iron Age (no prizes for guessing why so named!) commenced roughly 700BC in Britain and ended with the Roman invasion of 43AD. Iron Age archaeological sites are far more abundant than those of the more remote past, with certain hillforts still dominating modern landscapes. The Butser Ancient Farm project was designed to quantify the productivity of Iron Age arable farming, with the livestock being a secondary academic consideration but invaluable for public appeal and “cute factor”. Peter Jewell, a respected zooarchaeologist and later a founding member of RBST, was asked to advise on appropriate breeds. The Dexter was suggested as the only modern breed then available that approximated to the archaeological finds of cattle bones. Peter Jewell made it very clear at the time that small Kerry cattle would have been a better option but the parlous state of all rare breed cattle in the 1960’s meant that this was not possible. The Kerry had become too tall and the Dexter, though a better size, was too chunky in build.

Roman forts in northern England produce cattle bones in abundance, in comparison to the native Romano-British farmsteads which are generally sited on soils where animal bone does not survive. The graph below shows the range of withers heights estimated from the cattle metapodials, or cannon bones, from Vindolanda in the mid-section of the hinterland of Hadrian’s Wall and South Shields on the coast as the eastern defence. Both populations show a normal bell curve distribution with sufficient overlap to suggest no major difference in population between the two groups. However the range is important with examples both of the very tiny animals, that are affectionately referred to as “cow kittens” by some Dexter breeders, and very large animals at the other extreme. It cannot be emphasised too strongly that such a range is “normal” in biological terminology, irrespective of whether the very small animals may, or may not, be carriers of dwarfism. The fact that the shortest animals from South Shields fall below 0.98m, which is 2 Standard Deviations from the mean of 1.12m, could suggest the possibility of a form of dwarfism being present. What is clear is that this extremely small type, though present, was not being actively selected for, in contrast to the modern Dexter. This graph demonstrates one possible outcome of a strategy that has been suggested to reduce the incidence of achondroplasia in the modern Dexter, by eliminating the use of carrier bulls. Two possible carrier cows might be represented in a sample of 76 bones from South Shields. No unviable calves would be produced and the presence of carrier cows would continue at the same negligible incidence

Over the past 200 years, livestock breeders have interfered with the biologically normal range by endeavouring to breed animals that fit within a reduced range of height variation. In the Dexter this has been towards the smaller end of the range, but the same foundation population could equally have been bred towards the larger end of the range. In effect, this is how evolution works but the process is considerably speeded up by controlled breeding. The concept of a “level herd” is, in archaeological terms, a very modern concept.

The photograph above of the Doesmead herd in 1966, from Ted Neal’s book, is a very important image, showing a herd where selection for dairy production appears to have been considerably more important than looks. There is an interesting range of small and large, chunky and slender animals. This picture gives an idea of what the archaeological cattle represented in the graph could have looked like. The Doesmead herd further emphasises that selection in the Dexter for herds where all the animals are more or less the same size is a very recent phenomenon. It is therefore not surprising that, irrespective of the presence or absence of the dwarf gene, the modern Dexter should still exhibit a range of sizes both between herds and within herds, such as my own, where parameters other than height are seen as more important for selection and retention of breeding stock.